“A farm should be built around the manure system,” is the advice dairyman Jim Winn would give to someone planning to build a new dairy. “It’s the most important part.”

For Winn, successful partnerships have played a big role in his career as a life-long dairy farmer. An active leader in dairy circles, Winn immensely enjoys these opportunities to collaborate and meet other dairy farmers. He also sees value for the betterment of agriculture.

“It’s important,” he said. “We need a voice for dairy farmers.”

A group that Winn has worked with enthusiastically the past few years is the Lafayette Ag Stewardship Alliance. From its grassroots beginnings, the work of this farmer-led organization has made a difference not only on individual farms but has also created some inroads to connect environmentally conscious farmers with major players in food manufacturing.

A farmer-led effort

As a board member for the Edge Dairy Farmer Cooperative, Winn got to know Tim Trotter, executive director of the co-op and the Dairy Business Association. Recognizing his leadership abilities, Trotter reached out to Winn a few years ago, suggesting farmers in his area of southwestern Wisconsin think about starting a conservation group.

Considering the karst topography in Lafayette County that leads to groundwater quality concerns and his own passion for environmental stewardship, Winn acknowledged the need and took action. He contacted half a dozen of his farmer colleagues in the area, and they met for a lunch meeting at a local golf course. After tossing around some ideas, the Lafayette Ag Stewardship Alliance (known as LASA) was born in 2017.

Winn was named president, and a few other farmers joined him on a board of directors. Their organization established goals and scheduled their first event — a field day showcasing conservation farming techniques that reduce nutrient runoff and improve soil health. Winn said they didn’t know what to expect for participation but were pleasantly surprised when more than 100 people attended that day.

Over time, the group has grown from its original six members to more than 30, and Winn said they represent a wide array of farming operations. The farmer-led, nonprofit organization aims to protect natural resources, help the public understand general farming practices, and empower members to improve farming techniques.

Winn gave credit to several entities that help LASA be successful in its initiatives. “Working with The Nature Conservancy has been a huge benefit,” he explained, “and so is the Farmers for Sustainable Food non-profit organization.” He also recognized the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection for providing the grants that funded their group, and Trotter for his support of agriculture in general.

Winn said the positive impacts of LASA can be seen locally in many ways. One example of this is the use of cover crops. While Cottonwood Dairy has been utilizing cover crops, mostly rye and wheat, for well over a decade, he said more and more farms are adopting the practice now.

“Cover crops in the area just exploded, and I think LASA was a huge part of it,” he shared. A survey of LASA farmers in 2020 showed that cover crops were planted on 7,389 acres. Additionally, more than 29,000 acres were managed with conservation tillage practices, either strip or no-till planted in the spring, and almost 27,000 acres were covered by nutrient management plans.

A broader impact

Recently, the group has built bridges outside of the area as well. Grande Cheese Company, an Italian cheese manufacturer in eastern Wisconsin, was looking for opportunities to share with their customers the environmentally-friendly practices implemented on the farms providing their milk supply. This paired with LASA’s desire to track on-farm conservation practices and the impact they had on both the farming business and the local environment.

By combining forces, the Farmers for Sustainable Food, Grande Cheese Company, and the Lafayette Ag Stewardship Alliance were able to create “The Framework for Farm-Level Sustainability Projects.” This handbook helps farmers decide what conservation practices are most useful on their farm, document the environmental and financial impacts, and then showcase the value of sustainability through the food chain.

The pilot project included 12 farms and follows the model of a milkshed, representing the farms and businesses in the region that supply dairy foods to customers. The framework is flexible so that it can be replicated in other regions. The pilot project collected and analyzed farm data and wrapped up its first year in 2020. Current funding will take the project through 2022.

Winn explained that the framework gives farmers a tool to prove to themselves, to neighbors, and to milk purchasers that there is value in being innovative when it comes to manure management and environmentally friendly practices. He sees benefits in having milk processors and others in the supply chain moving in the same direction as farmers.

Others have noted the benefits, too. In fact, this pilot project was recognized nationally with an “Outstanding Supply Chain Collaboration” award presented by the Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy. These annual awards honor exceptional farms, businesses, and partnerships for their socially responsible, economically viable, and environmentally sound practices and technologies that have a broad and positive impact.

On an even bigger scale, Nestle, the world’s largest food and beverage company, has shown support for the project as part of its effort to partner with farmers, suppliers, and the industry to reduce the carbon footprint on farms. Their end goal is to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

Winn said their organization is proud of the changes and improvements that have been made in Lafayette County. Factor in the handbook project with Grande and Nestle and the national sustainability award, and Winn said, “That was huge for us. It put our organization’s name out there.”

Friends in business

Partnerships and stewardship are at the core of his own dairy farm, too.

From a young age, Winn knew that dairying was the career for him, even though two of his greatest farming role models — his father and grandfather — passed away early in Winn’s life. His mother and grandmother kept the farm running until Winn graduated high school and took over the reins.

His father and grandfather installed one of the very first parlors in Wisconsin in 1949, and Winn followed their innovative footsteps as he and his wife, Laurene, grew and renovated their farm.

From time to time, Winn and two fellow dairymen, cousins Brian Larson and Randy Larson, discussed partnering to build a dairy together. However, plans weren’t set into motion until after their financial lender recommended the three combine forces rather than expand their individual dairies.

Plans for that venture began in 1997, and the dairy was built the year after, on a 40-acre site that originally belonged to Brian’s dad. Independently, both Winn and Brian brainstormed the name Cottonwood Dairy, a nod to the cottonwood trees that used to grow nearby. Randy handles the financials, Brian the crops, and Winn manages the cow side of the dairy.

Their original expansion plans were met with opposition in their rural town, but they soon established a solid track record for environmental stewardship. They started with 600 cows, and a few years expanded to 900. Incremental growth over time led them to the 1,900 head that are housed on the farm today.

Calves are raised at the farm where Winn grew up and originally milked cows. At 5 months of age, they are moved to a heifer raiser before returning to the dairy.

Cows are milked three times a day in their double-20 parlor. The Holstein herd averages 98 pounds per cow per day, with 4.2% fat and 3.2% protein.

The herd’s somatic cell count averages 70,000 to 80,000 cells per milliliter. Winn credits teat scrubbers for having a huge effect on teat cleanliness and maintaining that low somatic cell count.

Bedding, and in particular clean bedding, also makes a difference. When they first built the dairy, cows rested on mattresses bedded with sawdust. By 2004, they switched to sand bedding, and Winn said the herd went up 10 pounds per cow in milk production practically overnight due to the improved cow comfort.

The switch to sand also necessitated some changes to their manure system. That same year, they built two sand lanes to recover and reuse the bedding. This has represented a huge cost savings; Winn projects they save hundreds of thousands of dollars a year in sand purchases. A few years later, they built a storage barn to save recycled sand for winter and only purchase new sand for their special needs barn.

Manure and used bedding are carried out of the barns with a flush flume system using reclaimed water, and the sand settling lanes separate the sand from the manure. The lanes are cleaned out every 12 hours, and the sand is first stacked next to the lanes, then moved to a concrete pad where it dries.

When using recycled sand, cleanliness is crucial. “The key to clean sand is to have clean water,” he shared. The water they use in their flush flume, which is stored in one of their manure lagoons, contains just 1.4% solids, and Winn’s goal is the keep that level under 2%. All water on the farm is recycled several times, and Winn noted, “That is another huge savings for us.”

All eyes on manure

When manure is flushed out of the freestall barns, it first goes into a 15,000 gallon tank, and this is where a polymer is added. Winn has used polymers for the last 16 years, and he said this is a major factor in producing cleaner recycled water. It helps separate the solids, and in the lagoons it also seals the solids at the top of the lagoon, reducing odor concerns.

From there, manure is pumped to the upper lagoon, where most of the solid manure is stored. Solid separators are used to remove more water. Much of the remaining water in the upper lagoon weeps into the lower lagoons through a pair of pipes, and this is where reclaimed water for the flume flush is stored. In all, the three lagoons have a total capacity of about 26 million gallons.

When Cottonwood Dairy was first established, the partners hired out all of the manure hauling. Then, they did their own application for a number years before choosing to hire custom operators again to save costs.

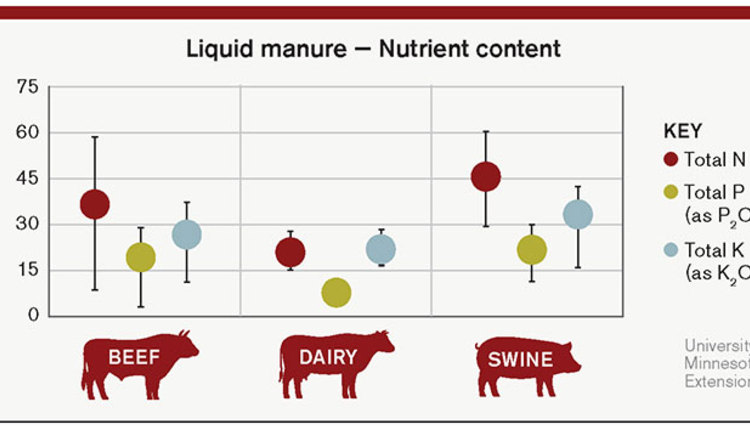

Almost all manure is applied using draglines, with just one 60-acre field farther away that requires trucking. Winn said they are able to do that one field quickly and keep the trucks off the road, which benefits the local community. In all, they operate about 2,500 acres of cropland, both owned and rented, and the nutrients in manure are an asset to them.

For the last 10 years, they have been using low disturbance manure injection. They also continue to dial down their rates of application every year, and Winn said they buy very little fertilizer. They have noticed positive differences in the crops grown in fields where manure was applied as opposed to commercial fertilizer, and some of their neighboring crop farmers have, too. Each year, manure from Cottonwood Dairy is applied to several neighbors’ fields as a nutrient source.

“We have always been very cautious stewards of the land,” said Winn,

and he remains open to new ideas when it comes to nutrient management. “Anything manure, I am all eyes and ears,” he said. Winn said he would like to incorporate more manure technology and would love to

generate gas if that was an option for them someday.

Introducing more manure processing opportunities to the area is one of Winn’s goals for LASA as well. The group will also continue to focus on nutrient management and maintaining quality of groundwater and surface water. Still further, the members hope to assure community residents that environmental stewardship is a priority for farmers, too.

Farmers working with other farmers, food processing partners, and national awards for collaboration all help get the word out, but Winn said more work can be done to share the conservation practices that are already implemented on most farms today. “It’s getting better and better, and farmers are finally getting some recognition,” Winn said, “but it’s time we tell our stories.”

This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Journal of Nutrient Management on pages 12 to 15.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.