Manure spills are a real obstacle for any livestock operation and any custom applicator. They may stop application for the day or require outside equipment to be hired for quick cleanup. Adding together the troublesome time costs and environmental impacts of manure spills, it is always worthwhile to look for ways to avoid them.

As an intern for University of Wisconsin-Madison Extension’s Conservation Professional Training Program, a previous intern (Racheal Osterhaus) and I researched manure spills and runoff incidents that happened in Wisconsin over a five-year period (2015 to 2019). We were looking for common issues and improvements that could be made. By looking through paper and electronic files kept by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) and county agencies, 729 spills were found. While evaluating these spills, we focused on collecting information about the root causes, impacts, and the commonalities between spills.

Where spills occur

The first piece of data to look at is where these manure spills take place. We broke the spills into three categories:

- During transport

- On the farm

- During or after application

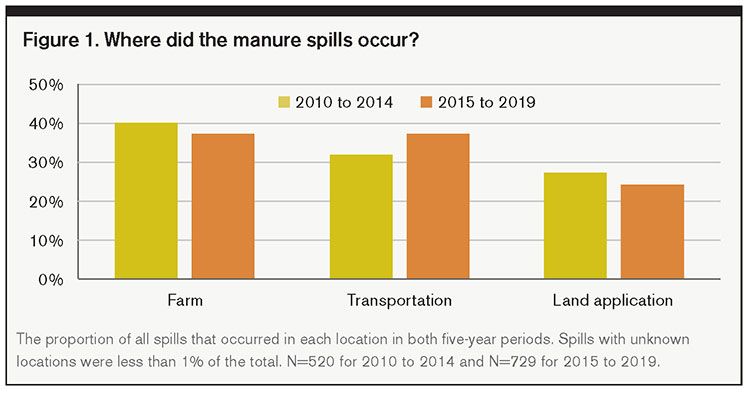

Spills most often happened when manure was being transported from the farm to the field (Figure 1). Problems during transportation include incidents like tankers tipping over, accidental valve openings, and dragline leaks. Transportation events have become more frequent, with transport being a cause in 38% of all spills from 2015 to 2019. That was up from 31% between 2010 and 2014.

On-farm spills followed closely behind in number of incidents, and between 2015 and 2019, this category represented another 38% of spills. Examples of these would be a manure storage overtopping, barnyard runoff, and transfer pipe failures. This is a smaller percentage of spills when compared to the 2010 to 2014 period, when 40% of spills occurred on the farm.

The final location for spills to happen was during or after land application. This is where problems like equipment breakdown or malfunction and runoff due to rain or snowmelt can occur. Overall, the percent of all spills from land application declined. From 2010 to 2014 land application represented 27% of incidents, but it fell to 23% of all spills from 2015 to 2019. Location was unable to be determined for the remaining 1% of manure spill incidents.

Tools and training

Extra focus on particular problems can help prevent spills. On-farm issues, like a manure storage overtopping, can be prevented with frequent monitoring of manure levels, equipment maintenance, and diverting as much clean water away from the manure storage as possible.

In a previous study (2005 to 2009), the number of manure storages overtopping in August (during summer with maximum evaporation) was just as high as in April. Implementation of weekly monitoring and installing markers in the manure storage that show the maximum operating level have made a significant difference.

During transportation, spills involving operator error, such as equipment tipping over and accidental valve openings, can be avoided with proper training and equipment familiarity. Spills that occur during or after land application, such as contaminated runoff leaving the field, can be reduced by checking resources like weather reports and manure spreading advisories each day. Injection and/or immediate incorporation also minimizes these risks.

The right reports

Focus should also be placed on reporting, so that proper cleanup is confirmed and possible environmental impacts can be prevented. The data we collected relies entirely on spills and runoff events that are reported and recorded.

Many pieces of data were collected to go along with each spill. Date and location were recorded, as well as information such as whether a custom manure hauler was involved and what sort of environmental impacts were observed.

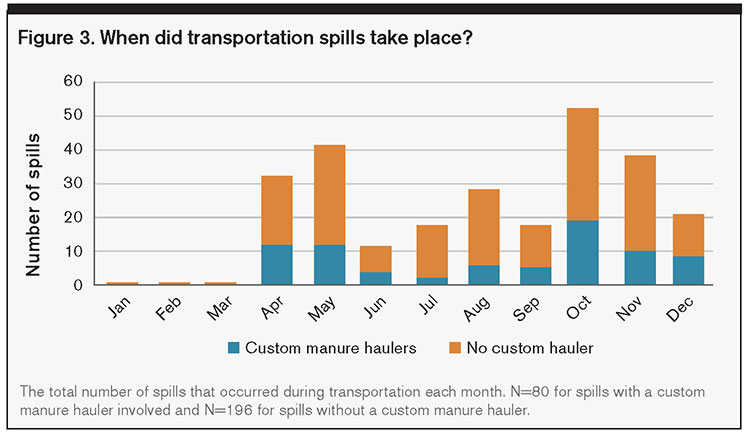

One of the clearer trends we found was the time of year that spills occurred. Most spills occurred in spring and fall, and specifically in the months of April, May, October, and November.

Another interesting trend was the involvement of custom manure haulers. Custom manure haulers transport over two-thirds of the manure in Wisconsin, but they were only a part of about 29% of spills during transportation (Figure 3).

Some other highlights include:

• Surface waters were impacted in 45% of spills (including road ditches with standing water that may not have connected to a stream).

- The most common spill volume was between 50 and 1,000 gallons.

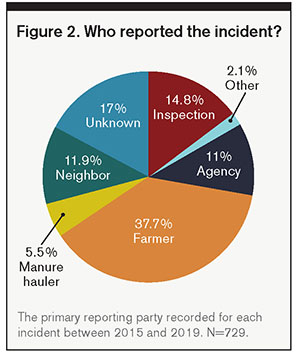

- Of the 729 spills, 62% went through the Wisconsin DNR spills telephone hotline.

- The years 2018 and 2019 were wetter than normal, and as a result, these two years alone represented 61% of manure storages overtopping between 2015 and 2019.

Goals of the project

This is the third five-year manure spill study conducted by the University of Wisconsin-Extension, in partnership with the Professional Nutrient Applicators Association of Wisconsin and the Wisconsin DNR. Despite the growing number of manure spill cases that have been recorded in each subsequent five-year study, experts and agency staff do not believe that the number of manure incidents is increasing. Instead, more spills are just being documented.

“Farmers and manure applicators are much more willing to self-report, because they’ve learned it’s the right thing to do and because it’s better to self-report than have a neighbor or citizen report a problem first,” noted University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension’s Kevin Erb.

This data will be used to refocus education efforts in the state and improve methods of recording and dealing with manure spills. The trends seen in Wisconsin could be used to help shape reporting and responses in other states as well.

This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Journal of Nutrient Management on pages 18 and 19.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.