We know that manure is rich in many nutrients and a valuable resource when applied back onto fields that can benefit from manure application. Research has demonstrated positive impacts to soil quality and health, crop production, and overall farm management when manure is managed effectively. There are, however, water quality and natural resource concerns related to the improper handling of manure.

In states where livestock farms are prominent, large amounts of manure are produced annually; most of this manure is applied back onto the fields for future crop production. Accounting for the nutrient content of manure and crediting that nutrient content toward the following year’s crop nutrient demand is imperative, both for farm profitability and environmental protection.

Content, availability, and value

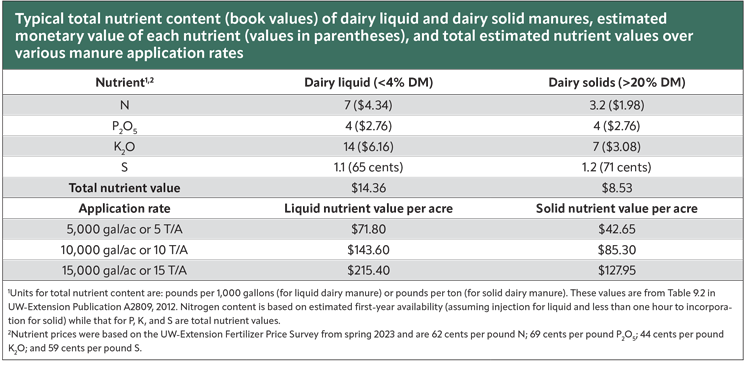

Nutrient content of manure is dependent on several factors, including animal species, incorporation method and timing (for nitrogen), and form (solid versus liquid). Manure nutrient book values are commonly used to give growers and nutrient management planners a “ballpark” idea as to what their manure nutrient content is. However, the best practice is to collect samples from each manure source on the farm and have them tested at an approved laboratory.

Recommended manure sampling methods can be found on the University of Wisconsin Soil and Forage Analysis Laboratory website, while a list of approved manure analysis laboratories can be found on the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection website.

Additionally, the total amount of nutrients in manure are generally not 100% available to crops; rather, a percentage of the total becomes available over a one- to three-year time period. Factors such as animal species, form, and application and incorporation practice influence nutrient availability of manure to crops. For more information related to typical nutrient content and nutrient availability of manure, please reference Chapter 9 in the UW-Extension Publication A2809 (Nutrient application guidelines for field, vegetable, and fruit crops in Wisconsin).

The value of livestock manure can be determined by comparing the nutrient value to your fertilizer prices. Using data from Table 1 for liquid dairy manure, a field receiving 10,000 gallons per acre would contribute about $143.60 per acre in total nutrient value, for example. Consider factors that can influence this monetary evaluation of manure as a resource, such as a change in fertilizer-nutrient prices, and expect fluctuations over time.

Water quality impacts

One reason to carefully manage manure is for the financial benefit, but another important reason is the potential impact it can have on water quality. Nitrates entering drinking water pose a human health risk, such as raised heart rate, nausea, headaches, and methemoglobinemia (also known as blue baby syndrome).

When excess phosphorus enters into streams, rivers, or lakes, it can cause eutrophication. This triggers plant and algae growth, negatively impacting the environment for fish and other aquatic species. A few examples where manure can contribute to water quality issues are over application of manure, manure application before a rainfall, and manure application on frozen soil.

Advice for spreading

Having multiple options to spread manure throughout the growing season is extremely valuable for the farmer and the environment. Options that allow spreading during better weather conditions, such as late spring and summer, are also when fields have more erosion-reducing vegetation coverage (to intercept raindrops) and a growing crop to immediately use the nutrients.

Spreading manure on growing plants means that plants can immediately take up the nutrients rather than leaving them vulnerable to moving off the field. During summer months, weather conditions tend to be drier and there is less chance of large runoff events, further reducing the risk.

Incorporating manure into a small grain or alternative forage rotation would also be a great option in summer months. Newer technologies and equipment allow spreading on standing crops without reducing yields. The Ohio State University has investigated different timings and ways to spread manure on standing corn. In a four-year study, they found that using a dragline to spread manure did not impact corn yields if used before the V5 stage.

Spreading manure in the fall after harvest leaves manure’s nutrients untouched by plants until the following spring and susceptible to losses via erosion or runoff. If spreading manure in the fall, choose fields that have a growing cover crop or have large amounts of crop residue on the surface. Wait until microbial activity slows down when soil temperatures cool (below 50°F), but apply manure before the soil freezes to help reduce nitrogen losses.

If possible, it’s best to not spread in the wintertime, once soil is frozen. Infiltration slows down or stops when the soil is frozen, which means that any rain that falls on frozen soil is more likely to run off the field. If manure must be spread, choose a location with a low slope that is well drained, far from surface water, and that has vegetative cover throughout the winter.

Over the years, many farms have fine tuned their manure handling process. If help is needed, the University of Wisconsin Soil Nutrient Application Planning Software (SnapPlus) has tools that provide recommendations on the best management practices related to manure. Ideally, manure and fertilizer should be applied as close to the crop’s nutrient uptake as possible, with application methods fine-tuned to reduce nutrient losses by erosion or to the atmosphere.

This article appeared in the February 2024 issue of Journal of Nutrient Management on pages 8-10. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.