In my early years in this business, “opportunity” may have been to site the open feedlot next to the creek. I think this original “flush-system” went the way of the moldboard plow. Now we are accountable for every pound of excrement and every drop of rain that comes into contact with manure. As a result, our lives and management systems became more complicated.

I wish there was one solution to fit all situations. The best I have experienced is dry poultry litters that compete very effectively with commercial fertilizers. With a myriad of manure “broker” businesses across the country that find homes for manure, it profits the producer, the broker, and the grain farm.

Room for it all

As livestock and poultry farms grew, they often relied on other farmers’ fields for distributing a portion, if not all, of their manure. That takes an element of control away from the manure producer, but good neighbors who understand manure value make life easier. However, I have discovered that even if you control all of the land needed to properly recycle manure, you can still make decisions that complicate the situation.

Having adequate storage until application fields are ready is imperative. When asked about minimum storage requirements, I advise clients that it’s about what they need to manage effectively, not just meet permit requirements. We all remember the wet springs we inevitably experience. As soon as the fields are dry, farmers want to plant corn, not wait on you to haul manure. What is your contingency plan if the fields are wet and the pit is full? This is when bad things happen.

Plant with purpose

Cropland is the key component to a manure management system. Don’t let it control you. Few things frustrate me more than when we know that manure will need to be applied mid-summer and the farmer says, “I can’t afford to plant wheat.” That may be true from a grain economics perspective, but alternative outlets will be more expensive.

Plan a crop rotation carefully to mesh with your manure application needs. One of my key points for land management is to plant at least 20% of a crop rotation in a small grain that is harvested mid-summer. This provides ideal soil conditions for manure applications and allows for deep or inversion tillage to deal with surface phosphorus accumulations. Then, follow with a cover crop to sequester manure nutrients for the future. It’s also a way to ensure that 40% of the acres are in a winter cover crop that has a direct economic value from grain and straw (or silage).

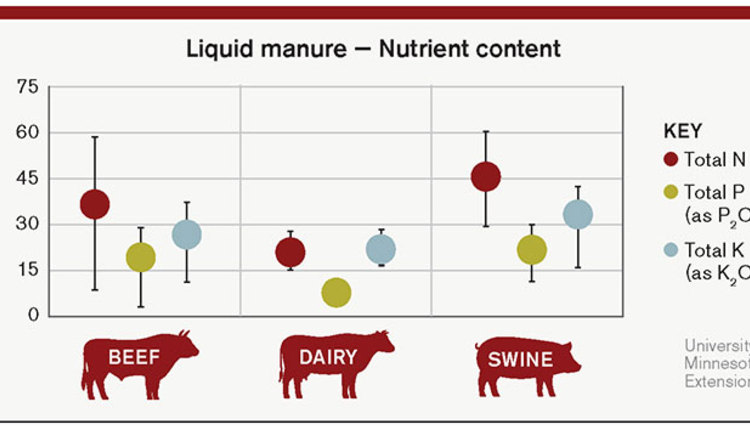

Looking at the liquid

There are innovative ways to integrate manure and crop management for liquid manures. We developed methods where manure solids are mechanically separated, followed by settling basins and then by an anaerobic treatment lagoon. Separated solids have high organic matter and low nutrients that can be applied to remote sites at high rates.

Settling basin “slurry” is nutrient dense, containing the majority of the phosphorus and is suitable for tanking further distances and applied at low rates. That leaves the treated lagoon water, a low nutrient water with low odor, to be irrigated at high rates on growing crops needing water. This comprises up to 70% of the manure volume with an application window of six months. That’s a big deal and a very economical application cost.

Planning is key to effective manure management. That includes integrating crop rotation, storage, treatment, and application methods together.

This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Journal of Nutrient Management on page 26.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.