The authors are educators with Michigan State University Extension.

Careful manure management is a principle of farm profitability and environmental stewardship. Thinking critically about your nutrient management plan can help protect your fields from the economic impact of nutrient loss and the resulting environmental impact.

One of the ways that researchers are exploring the retention of phosphorus is by observing the behavior of different sources of phosphorus fertilizers. Steve Safferman, a Michigan State University associate professor of engineering, has shown that mineral fertilizers (MAP and DAP) were statistically similar in both the degree of soil phosphorus retention and subsurface phosphorus loss through simulated tile drains. However, the phosphorus in organic fertilizers (dairy and swine manure) was bound to the soil at a higher degree and less likely to show up in the tile drain. In light of this research, let’s consider what role cover crops play in this system to improve our options or time frame to retain dissolved phosphorus.

Phosphorus and cover crops

Cover crops can help phosphorus conservation by taking up and storing nutrients for the primary crop. A 2015 study found that a wheat cover crop residue took up 20% to 40% of phosphorus in the soil, and 8% to 22% was utilized in the following crop. An older study found that a cover crop reduced the total phosphorus runoff by 36%.

Cover crops are efficient as short-term nutrient banks in crop fields. They should not be relied on to remove all excess phosphorus, though.

Nitrogen and cover crops

Farmers have adapted and changed their practices to address timing of nutrient applications and application methods. Applying manure to land that has a cover crop is another practice that can help with nitrogen management.

Minnesota researchers, led by Les Everett of the University of Minnesota Water Resource Center, wanted to determine the fate of nitrogen and if the nitrogen needs of the cash crop are met in the soil from injected manure with and without a cover crop. The research resulted in the following findings:

1. In both years, adequate growing seasons existed to establish the rye cover crop after either corn silage or soybean harvest, but aboveground fall growth was limited.

2. The rye was very resilient to manure injection; however, stand reduction was considerable at two sites where shank injectors or disk coverers were too aggressive.

3. At most sites, the spring rye growth did well, reducing soil nitrate under the cover crop compared to the check strips of all sites.

4. Rye growth and nitrogen uptake were greater in southern Minnesota compared to central Minnesota.

5. Across sites, there was not a significant difference in silage or grain yield between the cover crop and check strips.

Future research is required to assess the effects of cover crop termination methods and timing on nitrogen dynamics and performance of the subsequent corn crop. To obtain the full research report, visit on.hoards.com/nitrogenstudy.

Adoption of a cover crop scheme allows for a responsive cover in the event of sudden thaws that characterize winter in much of the Midwest. Cover crops proved to be effective in reducing nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N) loading through tile-drainage across the spectrum of common nitrogen fertilizer management systems.

Livestock farmers looking for ways to reduce the incidence of nitrogen leaching into groundwater from manure as well as phosphorus loss through tile drainage should consider cover crops as a tool in their toolbox.

Opportunities for feed

Cover crops that play a dual role as a forage can be harvested after the plant has taken up phosphorus. The biomass can then be fed to livestock, which recycles the phosphorus again in the following season through manure application leading to a more integrated crop and livestock system.

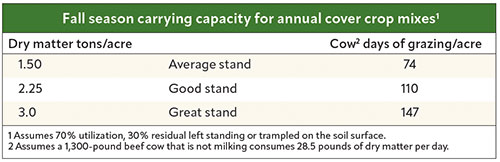

Annual cover crop mixtures can make very nutritious and economical grazing crops for spring, summer, fall, and early winter grazing in cool climates. Fall grazing is especially beneficial because it can fill the gap as perennial pasture grasses go dormant for winter. Tom Cook, a dairy farmer in central Michigan, says using cover crops as a forage after silage is taken off is a “no-brainer . . . utilizing the soil to get more nutrients and forage to feed the livestock.”

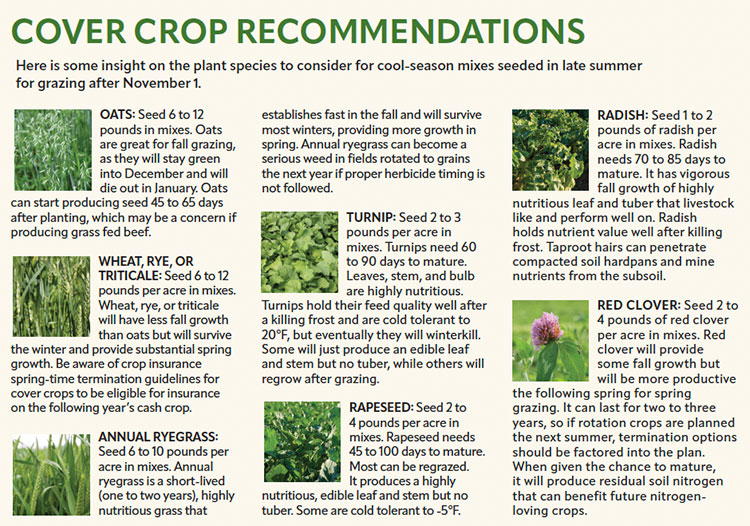

Mixes of four or more plant species all planted together at the same time and same depth at a seeding rate of 28 to 40 pounds per acre can be economical and nutritious for fall grazing livestock. These same mixes can also act as soil improvers, suppressing weed growth and mining nutrients from deep down in the subsoil, bringing them to the soil surface. With their aggressive growth, they also elevate soil organic matter both from the grazing animals’ manure and from the decaying plants’ leaves, stems, and roots.

Fall cover crops for grazing or chopping work best following a wheat harvest, oat harvest, or after silage. Depending on the species planted, you usually need 70 to 120 days of growth before temperatures drop into the low 20°F range. Plantings made from late July to mid-August turn out the best in cooler climates.

To provide a healthy, nutritious blend, consider a mixture of brassicas, small grains, legumes, and cool-season grasses. Be aware of possible drain tile plugging issues.

Plan to manage cover crop growth. Consider planting the cover crop in mid- to late August and schedule more intense grazing in fields where tile plugging may be a concern. Change the seed mix to include more shallow rooted species or winterkill cover crops.

Tile plugging from cover crops is very rare. A warm, late fall gives cover crops a long window for growth and increases the chances for roots to grow deep into the soil profile. Your local extension educator can help you find the right cover crop mix for your needs.

If rotating from a sod crop like hay or pasture, weed control is necessary. If seeding within 10 days of combining wheat or oats, it is not. The volunteer wheat or oat seed that was lost on the ground from the previous crop harvest can become part of the new seeding mix. Like any crop, the risk of insect and disease pressure will rise if the same plants are seeded on the same sites annually as the pests overwinter and attack their preferred food source.

Following soil test recommendations is always advised — these cover crops are expected to provide enough growth to feed livestock. Manure or 50 to 60 pounds of N/acre is usually a minimum requirement. The nonlegume plants really respond to nitrogen.

A word of caution

Be aware of livestock health risks that are dependent on the plant species used. Bloat, nitrate toxicity, and others are a possibility, especially if hungry animals overeat on a new pasture. To reduce risk, make sure livestock have a full stomach before turning them onto a new type of pasture and provide access to hay. In the seed mix, including oats and other grasses with brassicas and legumes also reduces the risk of bloat. When these precautions are followed, the risks are low.

Any time fields are grazed while wet, soil compaction can be a result, especially on heavier ground. Late fall and early winter grazing is often done in wet soil conditions, and some compaction will result. The best site locations are on lighter, well-drained soils. Research studies have shown that if grazing animals are pulled out during times of excess moisture, the benefits of fall grazing will outweigh the compaction issue. Soil fertility and crop yields often improve after cover crop grazing.

Soil health will benefit

The use of cover crops can be a valuable tool in building soil health and resilience. Cover crops supply feedstuffs, provide manure application opportunities, and they enhance the retention of nutrients. Soil degradation caused by intensive tillage and nutrient mining can be improved, and in turn, increase productivity through the use of cover crops and reduced tillage.

The ability to improve the biological, chemical, and physical soil properties can also improve nutrient efficiency in the system. These nutrient management benefits are especially important considering the USDA identified the Great Lakes Region as a Critical Conservation Area and has prioritized nutrient and sediment management on agricultural lands a top priority. A cover crop’s ability to reduce soil erosion by 90% and sediment transport by 75% makes them a useful tool on fallow ground that would otherwise be subjected to the elements and have the potential to further threaten this critical region.

Cover crops, in tandem with reduced tillage, maximize soil health improvement benefits and work toward accomplishing the goals of minimizing disturbance and maximizing soil cover, biodiversity, and the presence of living roots. This will ultimately prevent or mitigate compaction issues, as well as improve organic matter and water holding capacity.

“When we find out that we have an area with too much compaction . . . or water pools in an area . . . we will put cover crops in with radish or we will grow alfalfa to get those roots in there,” said Brent Wilson of Wilson Centennial Farms in central Michigan. “So, over time, we are trying to improve ourselves, and that’s a part of sustainability as far as I am concerned.”

This article appeared in the August 2022 issue of Journal of Nutrient Management on pages 16-18. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.