An unusual idea shared at a group meeting more than 25 years ago sent the Freund family and their dairy farm down a path of innovation and change that included the addition of a new business and a few brushes with fame along the way. This helped their family farm continue to develop in an area where herd growth wasn’t an option.

“In the early 1950s, it made all the sense in the world to be next to a river,” said Amanda Freund of the location near East Canaan, Conn., where her paternal grandparents, Eugene and Esther Freund, started farming in 1949. “But by 2000, that location was a lot less desirable.”

With a river that quite literally dissects their farm and a feed pad sitting right next to it, the Freunds worked extensively with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) over the years and fully embraced the environmental programs available to them. They also partnered with a group of livestock farmers to form the Canaan Valley Ag Cooperative with a focus on resource management. The farms were all located in the same watershed, and the state’s governmental leaders were growing increasingly concerned with agriculture and manure’s potential impact on water quality. Their proximity to a large population base in the Northeast made nutrient management even more imperative.

Each year, the group would gather with government officials, Connecticut Department of Agriculture staff, NRCS employees, and others to talk about current problems and possible solutions. These annual meetings brought different perspectives to the table, Freund noted. During one conversation about manure processing, a state employee from the Department of Agriculture asked, “Why don’t you make a flower pot out of it?”

The idea went in one ear and out the other for most at the meeting that day, but it resonated with Freund’s father, Matt, whose wife, Theresa, happened to own a garden center. That question got him thinking, “Why can’t we do this with our manure?”

Exploring the possibilities

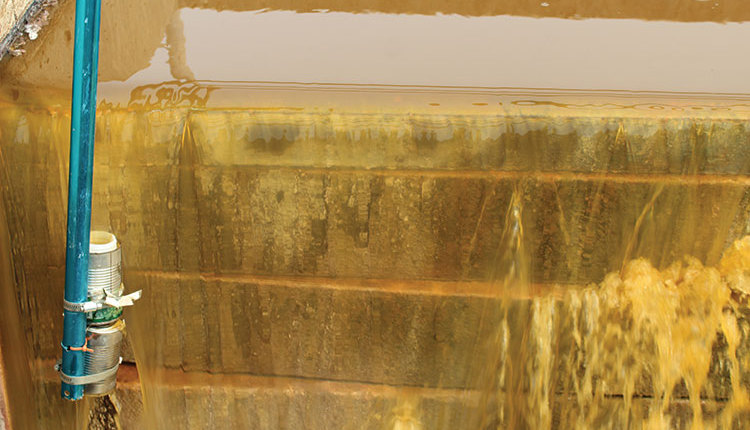

Matt and his brother, Ben, followed in their parents’ footsteps as owners of Freund’s Farm, and improved manure management has always been one of their priorities. Looking for a way to keep manure in a slurry state year-round, they installed one of New England’s first anaerobic digesters nearly 30 years ago. Manure is scraped from the barn’s alleys and trucked to the plug flow digester. A screw press then separates the solids from the digester effluent. The solids are used as bedding for the cows, and the liquid is applied to fields using draglines. “The installation of the digester made us more efficient in how we handled nutrients,” Freund explained.

For nearly three decades, the Freunds captured the biogas and burned it as renewable fuel. At its prime, the digester was providing enough gas to heat the farm’s hot water needs and the farmhouse. Today, the digester maintains its own heating needs.

Beyond bedding, the Freunds also started selling the solids as garden fertilizer to customers through their Freund’s Farm Market and Bakery. This is Theresa’s farm store that also includes 10 acres of gardens and a few greenhouses. People purchased the solids a pickup truckload at a time, and while it was not a big money maker, Freund said it moved some nutrient off the farm.

With this fiber source on hand and idea in mind, the Freunds went through years of trial and error as they researched the fibers in manure to create the perfect flower pot. They did their own research on site and also partnered with professors and students at the University of Connecticut and Cornell to test their prototype.

Eventually, CowPots were born. The Freunds’ patented process forms the digestate into biodegradable pots that are free of weeds and seeds and dissolve in the ground after planting, leaving behind nutrients for young plants. Their first 3-inch and 4-inch pots were sold in 2006. Today, CowPots come in 15 different shapes and sizes and are sold across the U.S. and internationally.

In the early years, pots were manufactured in one bay of the farm’s machine shop until a new building was constructed in 2008. The CowPots equipment was assembled by Matt Freund and a retired engineer. They designed it to be versatile, and all their current product offerings can be built with this machinery except for two that are made on the original pilot machine.

The production facility was designed to be zero-waste stream, explained Freund, with the only outputs being the finished product and water vapor from drying the pots. All used water is recycled and pots that don’t get packaged are reused as bedding and will eventually return to the manure system, becoming CowPots once again.

Production times have varied over the years depending on demand. The manufacturing facility currently runs five days a week for half the year. Their production employees make CowPots during the fall and winter and then spend spring and summer working in their retail business.

From the barn to the small screen

The Freunds packed their first CowPots into the back of the family’s van and drove around to garden centers trying to build their customer base. Catalog companies were also eager to advertise their product, Freund noted, and that was a great way to make sales back then. Today, CowPots are sold through distributors, retail customers, and their website.

While social media and the internet have many benefits, in some ways, it can be more difficult to capture people’s attention in this digital era, Freund noted. Although finding ways to promote their product to potential customers is still a work in progress, the fact that they are turning a waste stream into something valuable has opened the door to some fun marketing moments

“The whimsical nature of the product allows us to have some really cool opportunities,” Freund said. “It doesn’t take a lot of explanation for people to embrace the appeal of the product.”

Some may remember her father on an episode of the show “Dirty Jobs” with Mike Rowe. They also appeared on the “Today Show” and the “Martha Stewart Show,” and CowPots were featured in an article in The New York Times.

CowPots’ most recent claim to fame came in the form of an episode of “Shark Tank.” On this show, entrepreneurs pitch their products to a panel of wealthy business investors. If a contestant is successful, one of the “sharks” will make a deal for part ownership in their company.

Freund did not fill out an application to be on the show; her marketing consultant secretly applied for her. But alas, the application for a flower pot made from cow manure caught the production crew’s attention, and they followed up with Freund for a 30-minute call.

Over the next few months, Freund went through a series of meetings with the show’s casting team where they collect details and prepare candidates for their potential pitch. Freund noted that the process was extremely well organized, but it was also very time consuming as she met with the production team frequently and really dug into the gritty details of the CowPots operation. “I became a lot more familiar with the finances of our businesses through this process,” she said.

Freund did not find out she was invited to give her pitch until two weeks before the show’s taping, which took place in Los Angeles in September 2024. She could not tell anyone about the preparation and taping because she signed confidentiality agreements, and the filming experience was fast paced and intense. “It was one of the most stressful things I have ever done,” she shared.

The episode aired on April 4, 2025, at the height of gardening sales season. While the bump in sales after the show was brief, Freund was grateful to have the media exposure for their business.

If you watched the episode, you witnessed Freund accept a deal from Kevin O’Leary, known as “Mr. Wonderful” on the show. Following the recording, both parties did their due diligence, but a deal was not made between the Freunds and O’Leary after all. Freund said they were okay with that outcome.

“This operation is not a start-up,” she explained. “This is my dad’s legacy.” Before the show, she said they thought long and hard about how much of the business they’d be willing to split off and what they would need from a partner to skyrocket the business. “At the end of the day, I got what I wanted out of the experience,” she noted, which was an opportunity to introduce their product to a broad audience.

The show did open the door to some new business contacts. It also connected them with a family member, her great-grandmother’s niece who lived in California. The woman reached out after she saw the episode on television and ended up making the cross-country trip to visit the farm and family she hadn’t met before. Freund said it was a special moment that would not have taken place if it weren’t for the show.

Finding future pathways

Ten years ago, there were five members of the farm’s third generation sitting around the table with hopes to come back to the dairy. But over the years, plans changed, and after much thought, no family members decided to pursue farm ownership.

That opened a door for Ethan Arsenault, a young man from New York looking for an opportunity to farm. In search of someone to take over the farm, the Freunds called their friends Lloyd and Amy Vaill of Lo-Nan Farms in Pine Plains, N.Y. The Vaills partnered with Arsenault to form Canaan View Dairy in 2022. Together, they bought the 300-cow herd and rent the facilities from the Freunds, which includes an automated milking system and robotic feed pusher.

The Freunds continue to be involved in managing the dairy’s manure stream and the CowPots business. While Freund is excited about the future and the potential for their product, there are some hurdles that need to be addressed.

A big one is that the farm’s anaerobic digester, their fiber source, has far surpassed its life expectancy. The digester wears the title as the nation’s oldest operating digester, which is impressive but creates challenges as it does not function at its full potential anymore. The Freunds are looking into a replacement, but it is a huge investment, especially for a farm their size.

As for CowPots, Freund said the past 20 years have been a wild ride. “I wish I could say I had all the things figured out,” she said. However, they continue their uphill climb to build a customer base through avenues such as trade shows. At this time, Freund believes they are the only biodegradable pot manufactured in the United States. CowPots are an alternative to plastic and peat, which takes years to regenerate. Meanwhile, manure is produced on the dairy every single day, and being able to use that manure to make CowPots — and potentially other products in the future — is what excites Freund.

“I think this is the next generation of sustainability,” she said. “There are so many products that make claims about being renewable, recyclable, sustainable, or natural. This is what we are doing. We are taking a by-product from a dairy farm and transforming it into pots, but I also think about all the other purposes this product could serve.”

She is passionate about the impact dairy farms can have in this sustainability movement. “The capacity and opportunity and value that dairy farms can deliver goes well beyond the milk that leaves in a tanker,” Freund emphasized. “There continues to be so much critical attention on animal agriculture and greenhouse gas emissions. It’s such a narrow look at what a dairy farm has to contribute. By design, a dairy farm is meant to produce food, but it is so much more.”

She used Canaan View Dairy as an example. “For this farm to be a source of food, fertilizer, renewable energy, and a sustainable solution to plastic is really exceptional,” she said. “I just wish it wasn’t so hard to get more people on board to embrace this.”

Freund is motivated to carry on her family’s farming legacy and promote agriculture as a whole. Their dairy story has taken some creative turns along the way, and what started as one little idea bloomed into so much more. In a world looking for more sustainable solutions from agriculture, CowPots may be just the beginning for Freund and her family and what they can create with hard work, determination, and a little bit of cow manure.

This article appeared in the November 2025 issue of Journal of Nutrient Management on page 14.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.