The authors are with the USDA Agricultural Research Service.

The concept of a manureshed was developed to describe the amount of cropland needed to use the manure nutrients produced by a livestock operation without negative environmental impacts. Consider the manureshed as a cropland balance sheet to accommodate the nutrients from an operation’s manure.

Manuresheds have changed dramatically over time. Historically, dairies produced all, or most, of their own forages and feed. Manure nutrients could be reused for crop production on the farm without exceeding crop demand. So, the manureshed of these dairies was contained within individual farms.

Today’s manuresheds have grown. Trends toward larger farms in many regions of the U.S. have led to many dairies importing more forage and feed than in the past. The cropland available for manure application on individual dairies is often not sufficient to safely use the manure nutrients produced. In those cases, the manureshed becomes larger than the individual operation.

Manureshed area can vary greatly in different parts of the country. In regions that are dominated by small and medium-sized dairies, manuresheds generally remain small. However, the larger herds on many western U.S. dairies lead to large manuresheds.

Watching the water

Although the manureshed is a sound agronomic concept, its real relevance can be found in water. Water quality concerns are the main factor limiting the amount of manure nitrogen (N) and phosphorous (P) that can be safely applied. Phosphorus buildup in soil from years of manure application can elevate P in field runoff to water bodies where that P can trigger algal blooms and other harmful microbial growth. Another important concern is the leaching of nitrates to groundwater, especially in sandy soils or areas with shallow water tables.

The nutrient guidelines that have been developed in most states help farmers create manure and fertilizer application plans. These plans prevent excess nutrient accumulations and avoid application where the risk of nutrient losses is high.

Mapped by county

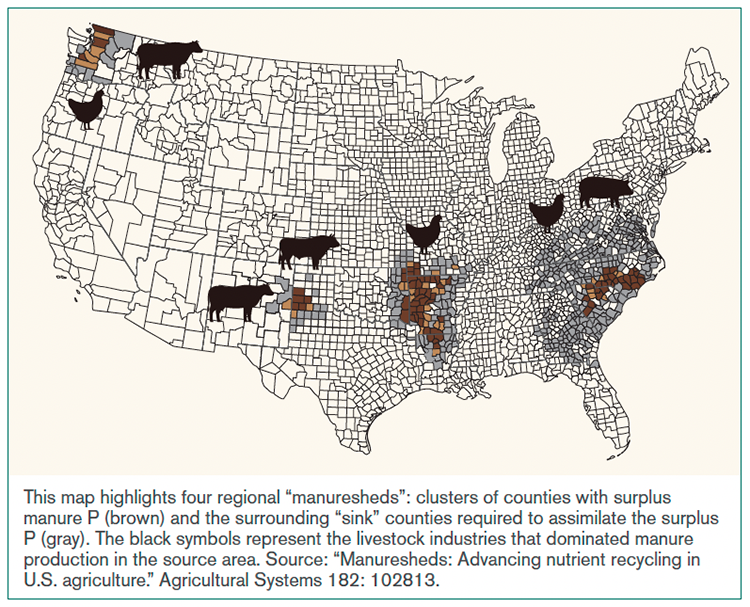

To understand the diversity of manuresheds within the United States, scientists from the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) evaluated nutrient balances at the county level. Using data from the USDA’s Census of Agriculture and International Plant Nutrient Institute, they estimated the amount of N and P excreted by each type of livestock in each county and compared that to the amount of the two nutrients that would be taken up by the crops grown in the county. This allowed them to determine if a county had nutrients in excess of the crop use (source counties) or if crops in the county have capacity to take up more nutrients than excreted by livestock (sink counties). The USDA ARS study showed that dairy production contributed to manure nutrient sources in about 200 counties across the U.S. However, in more than half of those counties, most manure came from other livestock.

The researchers went further to identify the cases in which several P source counties were adjacent to each other, and they treated those clusters as “source areas.” Then, for each source area, they calculated the number of nearby sink counties necessary to assimilate the surplus manure P from the source areas. A source area and its surrounding sink counties was deemed as a regional scale manureshed. Dairy was a dominant contributor of manure P in two of the major source areas, one in northwestern Washington and the other in the Texas Panhandle (see figure).

The researchers understand the limitations to their current analysis. Drilling down below the level of the county is not possible with these data; the Census of Agriculture and other USDA reports provide only county totals for manure and nutrient production and crop yields to protect producer confidentiality. Accordingly, the study did not remove counties with croplands with high soil P from the list of potential sinks, as soil P is not reported except at very general levels of spatial resolution. But the authors maintain that the regional manuresheds they identified were consistent with moving manure P away from counties where P would likely have built up in soils associated with dairy production to counties where that manure P could substitute for fertilizer in crop production.

These limitations mean that they are using other approaches to better understand nutrient balances and manureshed requirements for individual farms. For instance, they have used computer simulation models with data from example farms to estimate nutrient balances across a wide range of management types and herd sizes.

Moving manure

The manureshed offers a framework for understanding the need to move manure, but many factors can complicate manure trading. For instance, although manure is a terrific fertilizer resource, it often contains water that dilutes its nutrient content, may not match the nutrient requirements of the crops to which it is applied, and may bring certain liabilities, including odor, weed seed, and even pathogens. So, manureshed management is a complicated thing.

Moreover, the distance that manure must be transported can also vary widely. In the Great Lakes and northeastern U.S., dairies are typically close to crop farms that could apply excess manure in place of commercial fertilizers. However, many western dairies import feeds from distant locations and do not have sufficient local croplands to safely use the manure produced. In those cases, manure must be transported longer distances.

Manure processing on the farm can dramatically improve the value of manure and its potential for off-farm transport. On farms where liquid manure handling systems are common, the water content adds to the cost of transportation. Equipment for dewatering manure is widely available and reduces the volume of manure transported.

Composting can create a value-added product from manure with markets for specialty crop production and home gardening. Technologies available to remove nutrients from manure and concentrate them into fertilizer products with commercial value is an alternative that is also being developed.

Communication networks to connect livestock producers with farmers who could use the manure nutrients are paramount for facilitating nutrient redistribution. Manureshed analysis, along with other nutrient management tools, gives farmers and technical service providers a tool to consider the opportunities and barriers for manure redistribution and potentially improve the chances for meeting a variety of environmental and production goals.

This article appeared in the May 2022 issue of Journal of Nutrient Management on pages 12 & 13. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.